Malaria, Cancer, Alzheimer's, Influenza, Measles, Ebola, AIDS, Cystic Fibrosis.....How do we decide what to investigate?

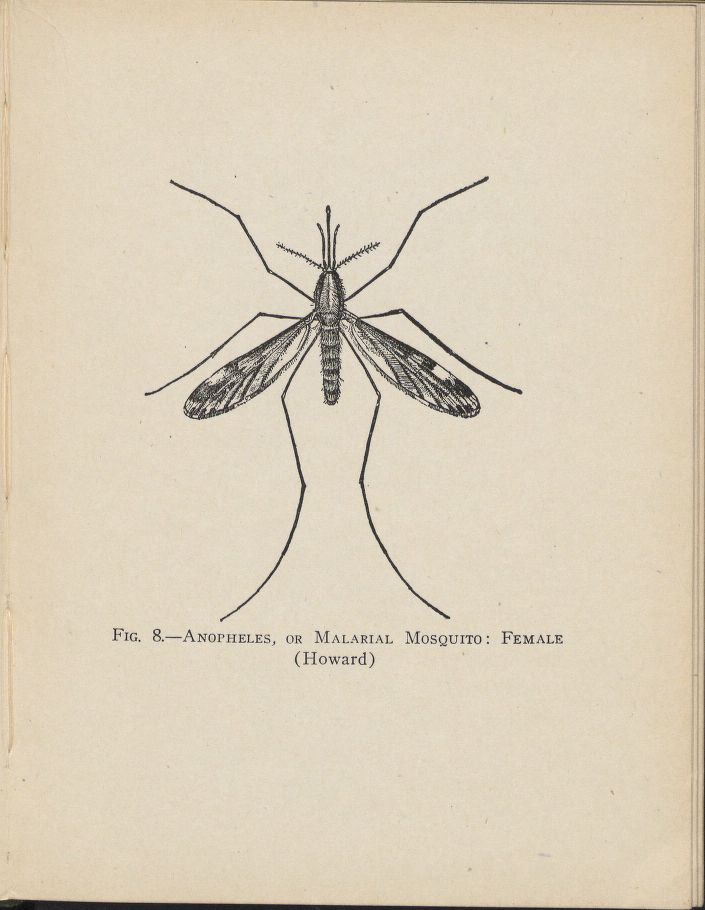

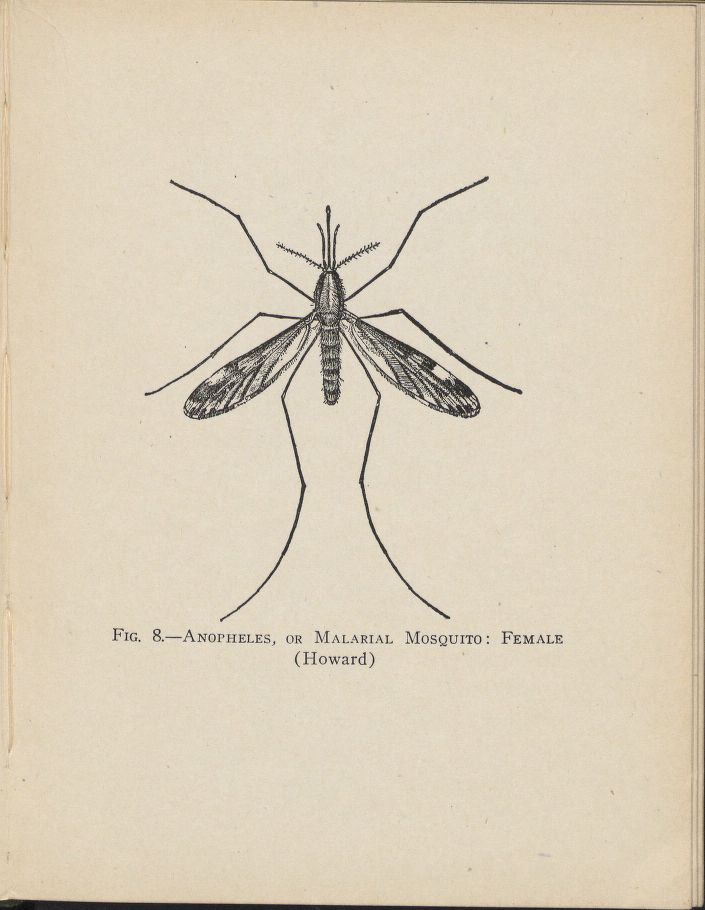

As you start your new year at the UTC, you will be no doubt be aware of the theme that will pervade the first half term: the Global Challenge of Malaria. I am sure that most of you will have a picture in your mind of African villagers dealing with a health crisis in challenging circumstances. I wont think of the prospect of catching malaria while you sleep in your own bed, but you might wonder if you are likely to catch measles from a classmate, or more likely the flu or a cold. We know that certain diseases are restricted to some parts of the world (by restricted I should really say that they are much more prevalent), some are dangerous to infants and some, like Alzheimer's disease are rarely found in adults under the age of 60. It is really important that you develop a perspective on the "significance" of a health problem. This is the theme of this Blog: I want you to be able to decide for yourselves with evidence, which areas of Medicine and Science are important. I also want to alert you to the ways in which new discoveries arise, the impact they might have on the quality of our own and the lives of others across the world. I also want you to understand why sometimes we need to investigate things out of pure curiosity, since it is from this route that many of our current technologies arose in the first place. However, ultimately, research costs money and it is the tax payer that decides how much money we invest in research. And as Benjamin Franklin said: "In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes".

As you start your new year at the UTC, you will be no doubt be aware of the theme that will pervade the first half term: the Global Challenge of Malaria. I am sure that most of you will have a picture in your mind of African villagers dealing with a health crisis in challenging circumstances. I wont think of the prospect of catching malaria while you sleep in your own bed, but you might wonder if you are likely to catch measles from a classmate, or more likely the flu or a cold. We know that certain diseases are restricted to some parts of the world (by restricted I should really say that they are much more prevalent), some are dangerous to infants and some, like Alzheimer's disease are rarely found in adults under the age of 60. It is really important that you develop a perspective on the "significance" of a health problem. This is the theme of this Blog: I want you to be able to decide for yourselves with evidence, which areas of Medicine and Science are important. I also want to alert you to the ways in which new discoveries arise, the impact they might have on the quality of our own and the lives of others across the world. I also want you to understand why sometimes we need to investigate things out of pure curiosity, since it is from this route that many of our current technologies arose in the first place. However, ultimately, research costs money and it is the tax payer that decides how much money we invest in research. And as Benjamin Franklin said: "In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes".

The scale of a health problem often dictates the priority given to research and financial investment. As a new University lecturer, a Head of Department will have recruited you partly because you have impressed at interview, but increasingly because you are working on a problem that is seen to be fundable. So what are the priorities of the UK funding agencies? Life Sciences in Universities and Research Institutes in the UK are funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Medical Research Council (MRC), the Natural and Environmental Research Council (NERC) and the Wellcome Trust. There are differences in their priorities but they all agree that Human and Animal Health are a priority, with new antibiotics and resistance mechanisms, together with ageing research, receiving a great deal of attention. Cancer Research is the primary focus of Cancer Research UK (CRUK), with different Research Centres specializing in the various forms of cancer, eg lung cancer, bowel cancer, pancreatic cancer etc. You will notice that I haven't mentioned malaria or ebola. This is where the challenge of obtaining funding becomes more complex.

The scale of a health problem often dictates the priority given to research and financial investment. As a new University lecturer, a Head of Department will have recruited you partly because you have impressed at interview, but increasingly because you are working on a problem that is seen to be fundable. So what are the priorities of the UK funding agencies? Life Sciences in Universities and Research Institutes in the UK are funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Medical Research Council (MRC), the Natural and Environmental Research Council (NERC) and the Wellcome Trust. There are differences in their priorities but they all agree that Human and Animal Health are a priority, with new antibiotics and resistance mechanisms, together with ageing research, receiving a great deal of attention. Cancer Research is the primary focus of Cancer Research UK (CRUK), with different Research Centres specializing in the various forms of cancer, eg lung cancer, bowel cancer, pancreatic cancer etc. You will notice that I haven't mentioned malaria or ebola. This is where the challenge of obtaining funding becomes more complex.

The history of Tropical Disease Research in the UK is an interesting one, and one in which Liverpool has been centre stage. Over 100 years ago, shipping merchants who relied on the health of their crew for their business successes, identified "tropical diseases" as a major threat. In those days Britain's influence was just as global as it is today, but it was in the context of the British Empire, which required a radically new solution for protecting the health of commonwealth citizens, and in particular the various professionals and troops who governed countries that became lucrative sources of produce and raw materials for the increasingly industrialised "West". This led to the foundation of the Liverpool and then London Schools for studying and developing methods for preventing and treating rare, Tropical Diseases. These institutions were also critical in supporting the health of the armed forces during the two major (and many minor) wars of the last century.Today, they play a key role in both educating and providing advice to international organisations such as the World Health Organization as well as controlling the global spread of such diseases, in the context of international travel which is now commonplace in the West. In short the stability of the population of the world as a whole isn't a National issue, it is global.

The history of Tropical Disease Research in the UK is an interesting one, and one in which Liverpool has been centre stage. Over 100 years ago, shipping merchants who relied on the health of their crew for their business successes, identified "tropical diseases" as a major threat. In those days Britain's influence was just as global as it is today, but it was in the context of the British Empire, which required a radically new solution for protecting the health of commonwealth citizens, and in particular the various professionals and troops who governed countries that became lucrative sources of produce and raw materials for the increasingly industrialised "West". This led to the foundation of the Liverpool and then London Schools for studying and developing methods for preventing and treating rare, Tropical Diseases. These institutions were also critical in supporting the health of the armed forces during the two major (and many minor) wars of the last century.Today, they play a key role in both educating and providing advice to international organisations such as the World Health Organization as well as controlling the global spread of such diseases, in the context of international travel which is now commonplace in the West. In short the stability of the population of the world as a whole isn't a National issue, it is global.

We mustn't just consider research funding at academic institutions. What are the economic factors behind the growth of the Pharmaceutical sector into one of Britain's largest employers and most successful businesses? (I have touched on this issue elsewhere on these pages, and at my Molecules to Market Blog page). Clearly, just like any other "for-profit" business, a drug company must make sufficient money from the whole process of drug discovery from sales, and this is determined by the cost of development, meeting the regulatory requirements (through clinical trials) and subsequently marketing the drug at a suitable price. Given that the cost of bringing a drug to market can be several billion dollars, the pharmaceutical industry is in many ways a challenging one. It may not surprise you to learn that the focus for new drugs is driven by market size and ability of that population to pay for such high cost new drugs. It is thanks to major interventions by high profile advocates like Bill Gates, that diseases like malaria are now on the agenda of drug companies who would otherwise see malaria treatment as a high risk market.

We mustn't just consider research funding at academic institutions. What are the economic factors behind the growth of the Pharmaceutical sector into one of Britain's largest employers and most successful businesses? (I have touched on this issue elsewhere on these pages, and at my Molecules to Market Blog page). Clearly, just like any other "for-profit" business, a drug company must make sufficient money from the whole process of drug discovery from sales, and this is determined by the cost of development, meeting the regulatory requirements (through clinical trials) and subsequently marketing the drug at a suitable price. Given that the cost of bringing a drug to market can be several billion dollars, the pharmaceutical industry is in many ways a challenging one. It may not surprise you to learn that the focus for new drugs is driven by market size and ability of that population to pay for such high cost new drugs. It is thanks to major interventions by high profile advocates like Bill Gates, that diseases like malaria are now on the agenda of drug companies who would otherwise see malaria treatment as a high risk market.

So research into diseases is driven in part my national and international agenda in different ways and in addition, we rely on the drug companies to find ways of short circuiting the discovery and development phases, in order to keep their costs down. What room is there for serendipity in Life Science research? In respect of diseases, the work on ebola, that I discussed in my previous blog illustrates how a disease caused by a potent virus has begun to unearth new concepts in fundamental molecular biology. The disease affects a very small number of individuals annually, and is a very minor cause of death in comparative terms. It would therefore be unlikely to receive the same kind of funding as cancer research. Nevertheless, I think the work on ebola illustrates that if your ideas are sound and creative, it is still possible to attract the necessary funding, in the right environment, to make important, non-mainstream, fundamental discoveries. It is important for you as our future scientists that you are as well informed as possible, not only about how to do experiments, but why they should be done and to be aware of the forces that drive scientific discovery and remember as Louis Pasteur said: "Chance favours only the prepared mind".

So research into diseases is driven in part my national and international agenda in different ways and in addition, we rely on the drug companies to find ways of short circuiting the discovery and development phases, in order to keep their costs down. What room is there for serendipity in Life Science research? In respect of diseases, the work on ebola, that I discussed in my previous blog illustrates how a disease caused by a potent virus has begun to unearth new concepts in fundamental molecular biology. The disease affects a very small number of individuals annually, and is a very minor cause of death in comparative terms. It would therefore be unlikely to receive the same kind of funding as cancer research. Nevertheless, I think the work on ebola illustrates that if your ideas are sound and creative, it is still possible to attract the necessary funding, in the right environment, to make important, non-mainstream, fundamental discoveries. It is important for you as our future scientists that you are as well informed as possible, not only about how to do experiments, but why they should be done and to be aware of the forces that drive scientific discovery and remember as Louis Pasteur said: "Chance favours only the prepared mind".

As you start your new year at the UTC, you will be no doubt be aware of the theme that will pervade the first half term: the Global Challenge of Malaria. I am sure that most of you will have a picture in your mind of African villagers dealing with a health crisis in challenging circumstances. I wont think of the prospect of catching malaria while you sleep in your own bed, but you might wonder if you are likely to catch measles from a classmate, or more likely the flu or a cold. We know that certain diseases are restricted to some parts of the world (by restricted I should really say that they are much more prevalent), some are dangerous to infants and some, like Alzheimer's disease are rarely found in adults under the age of 60. It is really important that you develop a perspective on the "significance" of a health problem. This is the theme of this Blog: I want you to be able to decide for yourselves with evidence, which areas of Medicine and Science are important. I also want to alert you to the ways in which new discoveries arise, the impact they might have on the quality of our own and the lives of others across the world. I also want you to understand why sometimes we need to investigate things out of pure curiosity, since it is from this route that many of our current technologies arose in the first place. However, ultimately, research costs money and it is the tax payer that decides how much money we invest in research. And as Benjamin Franklin said: "In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes".

As you start your new year at the UTC, you will be no doubt be aware of the theme that will pervade the first half term: the Global Challenge of Malaria. I am sure that most of you will have a picture in your mind of African villagers dealing with a health crisis in challenging circumstances. I wont think of the prospect of catching malaria while you sleep in your own bed, but you might wonder if you are likely to catch measles from a classmate, or more likely the flu or a cold. We know that certain diseases are restricted to some parts of the world (by restricted I should really say that they are much more prevalent), some are dangerous to infants and some, like Alzheimer's disease are rarely found in adults under the age of 60. It is really important that you develop a perspective on the "significance" of a health problem. This is the theme of this Blog: I want you to be able to decide for yourselves with evidence, which areas of Medicine and Science are important. I also want to alert you to the ways in which new discoveries arise, the impact they might have on the quality of our own and the lives of others across the world. I also want you to understand why sometimes we need to investigate things out of pure curiosity, since it is from this route that many of our current technologies arose in the first place. However, ultimately, research costs money and it is the tax payer that decides how much money we invest in research. And as Benjamin Franklin said: "In this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes". The scale of a health problem often dictates the priority given to research and financial investment. As a new University lecturer, a Head of Department will have recruited you partly because you have impressed at interview, but increasingly because you are working on a problem that is seen to be fundable. So what are the priorities of the UK funding agencies? Life Sciences in Universities and Research Institutes in the UK are funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Medical Research Council (MRC), the Natural and Environmental Research Council (NERC) and the Wellcome Trust. There are differences in their priorities but they all agree that Human and Animal Health are a priority, with new antibiotics and resistance mechanisms, together with ageing research, receiving a great deal of attention. Cancer Research is the primary focus of Cancer Research UK (CRUK), with different Research Centres specializing in the various forms of cancer, eg lung cancer, bowel cancer, pancreatic cancer etc. You will notice that I haven't mentioned malaria or ebola. This is where the challenge of obtaining funding becomes more complex.

The scale of a health problem often dictates the priority given to research and financial investment. As a new University lecturer, a Head of Department will have recruited you partly because you have impressed at interview, but increasingly because you are working on a problem that is seen to be fundable. So what are the priorities of the UK funding agencies? Life Sciences in Universities and Research Institutes in the UK are funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), the Medical Research Council (MRC), the Natural and Environmental Research Council (NERC) and the Wellcome Trust. There are differences in their priorities but they all agree that Human and Animal Health are a priority, with new antibiotics and resistance mechanisms, together with ageing research, receiving a great deal of attention. Cancer Research is the primary focus of Cancer Research UK (CRUK), with different Research Centres specializing in the various forms of cancer, eg lung cancer, bowel cancer, pancreatic cancer etc. You will notice that I haven't mentioned malaria or ebola. This is where the challenge of obtaining funding becomes more complex.  The history of Tropical Disease Research in the UK is an interesting one, and one in which Liverpool has been centre stage. Over 100 years ago, shipping merchants who relied on the health of their crew for their business successes, identified "tropical diseases" as a major threat. In those days Britain's influence was just as global as it is today, but it was in the context of the British Empire, which required a radically new solution for protecting the health of commonwealth citizens, and in particular the various professionals and troops who governed countries that became lucrative sources of produce and raw materials for the increasingly industrialised "West". This led to the foundation of the Liverpool and then London Schools for studying and developing methods for preventing and treating rare, Tropical Diseases. These institutions were also critical in supporting the health of the armed forces during the two major (and many minor) wars of the last century.Today, they play a key role in both educating and providing advice to international organisations such as the World Health Organization as well as controlling the global spread of such diseases, in the context of international travel which is now commonplace in the West. In short the stability of the population of the world as a whole isn't a National issue, it is global.

The history of Tropical Disease Research in the UK is an interesting one, and one in which Liverpool has been centre stage. Over 100 years ago, shipping merchants who relied on the health of their crew for their business successes, identified "tropical diseases" as a major threat. In those days Britain's influence was just as global as it is today, but it was in the context of the British Empire, which required a radically new solution for protecting the health of commonwealth citizens, and in particular the various professionals and troops who governed countries that became lucrative sources of produce and raw materials for the increasingly industrialised "West". This led to the foundation of the Liverpool and then London Schools for studying and developing methods for preventing and treating rare, Tropical Diseases. These institutions were also critical in supporting the health of the armed forces during the two major (and many minor) wars of the last century.Today, they play a key role in both educating and providing advice to international organisations such as the World Health Organization as well as controlling the global spread of such diseases, in the context of international travel which is now commonplace in the West. In short the stability of the population of the world as a whole isn't a National issue, it is global. We mustn't just consider research funding at academic institutions. What are the economic factors behind the growth of the Pharmaceutical sector into one of Britain's largest employers and most successful businesses? (I have touched on this issue elsewhere on these pages, and at my Molecules to Market Blog page). Clearly, just like any other "for-profit" business, a drug company must make sufficient money from the whole process of drug discovery from sales, and this is determined by the cost of development, meeting the regulatory requirements (through clinical trials) and subsequently marketing the drug at a suitable price. Given that the cost of bringing a drug to market can be several billion dollars, the pharmaceutical industry is in many ways a challenging one. It may not surprise you to learn that the focus for new drugs is driven by market size and ability of that population to pay for such high cost new drugs. It is thanks to major interventions by high profile advocates like Bill Gates, that diseases like malaria are now on the agenda of drug companies who would otherwise see malaria treatment as a high risk market.

We mustn't just consider research funding at academic institutions. What are the economic factors behind the growth of the Pharmaceutical sector into one of Britain's largest employers and most successful businesses? (I have touched on this issue elsewhere on these pages, and at my Molecules to Market Blog page). Clearly, just like any other "for-profit" business, a drug company must make sufficient money from the whole process of drug discovery from sales, and this is determined by the cost of development, meeting the regulatory requirements (through clinical trials) and subsequently marketing the drug at a suitable price. Given that the cost of bringing a drug to market can be several billion dollars, the pharmaceutical industry is in many ways a challenging one. It may not surprise you to learn that the focus for new drugs is driven by market size and ability of that population to pay for such high cost new drugs. It is thanks to major interventions by high profile advocates like Bill Gates, that diseases like malaria are now on the agenda of drug companies who would otherwise see malaria treatment as a high risk market.

You may recall that Perkin's ambitious but doomed attempt to synthesize quinine in 1856 led instead to mauveine and the foundation of the synthetic dyestuff industry. He was eighteen years old! Yet it surprised me that the first entirely stereoselective total synthesis of (-)-quinine was reported only in 2001. "Quinine has occupied a central place among the many plant alkaloids which are used in medicine. For over three centuries, and until relatively recently, it was the only remedy available to deal with malaria, a disease from which millions have died. Rational attempts to synthesize quinine started early in the first half of the twentieth century and eventually resulted in total syntheses in which 3 of the 4 asymmetric centers in the molecule were established stereoselectively. An entirely stereoselective synthesis of quinine has, however, not yet been achieved. This paper reports our successful efforts to meet this challenge."

ReplyDelete(J. Amer. Chem. Soc. 2001,123, 3239-3242). An interesting inter-play between academic and industrial medicinal chemists over a long period.

I also recalled reading that the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum obtains almost all its amino acid requirements by degrading host cell haemoglobin: the exception is isoleucine, which surprisingly is not present in adult human haemoglobin. Interfering with exogenous isoleucine may therefore provide a route to antimalarial drug development. (For example, PNAS 2011, 108(4), 1627).

Why human haemoglobin contains no isoleucine is another matter ...